HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 05) Año 2016. Pág. 12

Antônio Carlos DIEGUES 1; José César CRUZ Júnior 2; José Eduardo ROSELINO 3; Luís Felipe Lopes MILARÉ 4; Caroline Miranda BRANDÃO 5

Recibido: 06/10/15 • Aprobado: 26/10/2015

1. Chinese industrialization process

2. The Brazilian Industrial Development Impasse

ABSTRACT: This paper aims to present a synthetic view of the Chinese and Brazilian industrialization paths, highlighting the determinants of the different development trends for both nations. Based in a comparative analisys of indicators as sectorial composition of industrial value added, industrial production value and exports, the main conclusion is that, since 1990's, China has improved its production and exports in high technology goods, while Brazil has increased the share of production and exports in low skill technology goods. This shows the main differences in performance of innovation, GDP growth and importance of industry between those countries. Palavras chaves: China; Brazil; industrial development; innovation; international trade; cathing-up. |

RESUMO: O objetivo deste artigo é apresentar uma visão acerca das trajetórias de industrialização chinesa e brasileira. A partir da comparação de diversos indicadores como a composição setorial do valor bruto da produção industrial, do valor adicionado e das exportações, conclui-se que desde os anos 1990, a China aumentou sua produção de bens intensivos em tecnologia, enquanto o Brasil aumentou a sua participação em setores de baixa intensidade tecnológica. Assim, é possível verificar as diferenças de desempenho em inovação, crescimento do PIB, além de importância da indústria, nos dois países. |

China is widely known for its increasing growth rates since 1980s. The country has faced a GDP growth of 7,7% per year, between 2010 to 2014 (WORLD BANK, 2014). This strong growth fosters debate in international economic literature about its causes.

Since the 1980's the Chinese government has being making efforts in order to increase the industrial production of high-technology based goods and to strength the domestic industry. The impacts of such policies can be seen through the increase in the Chinese industrial production as well as in the improvement of the exports qualities, towards more sophisticated goods.

Unlike China, Brazil has faced a lower growth rate of its GDP, which was 2,5% per year, from 2010 to 2014. Such low performance brought the country's economy to a crossroad. After a few decades of advance, when a complex and integrated manufacture sector was built, the Brazilian industry is now showing a regressive restructure, and has been specializing in sector with low technological intensity, mainly based in the use of natural resources.

The economic condition described has multiple determinants, among which we can mention the neoliberal reforms implemented during the 1990s, and the macroeconomic policy related to a persistent currency appreciation and high interest rates. So, even after the return of an industrial policy on the political agenda on the last decade, the country was unable to stop this process of loss of density in production chains of technologically complex sectors with higher productivity and great dynamism in the international market.

In this context, this paper aims to present a synthetic view of Chinese and Brazilian industrialization paths, highlighting the determinants of the different development trends for both nations.

As a theoric referential, the paper bases its argument in the assumption that, as Rodrik (2007) says, the decisions concerning industrial policies are closely related to the structural differences in performance and in the potential of industrial diversification in developing countries.

Over the last decades China faced a powerful industrial transformation as part of its development strategy. During the most recent years, the Chinese industry was able to start acting in certain market segments considered as more advanced in terms of technology. Many authors recognize that in the 80's an important part of Chinese products that could be found on the market were basically textiles. During the 90's, however, it was very common to find products more intensive in technology, such as toys, electronics and other machines. During the first decade of the 2000's the Chinese industry has been able to produce more complex machines, vehicles, as well as airplanes. In order to built a portfolio of products, the Chinese industry has evolved to a more complex and productive structure with a greater presence of high technology sectors in its composition. This transformation is being accomplished due to a series of reforms made by the Chinese policy makers since Deng-Xiaoping's government.

Deng Xiaoping was responsable for in opening China economy to the world. During this period, the Special Economic Zones (SEZs) were created to attract international investment (Foreign Direct Investment) in some specific territories. Companies were driven to produce in China because they had many benefits from producing in China, such as, depreciated exchange rate, tax exemption, and local low wages (MILARÉ, 2012). This was China's attempt to modernize its industrial park through the investment of international companies. As pointed out by Acioly (2005, p. 27 apud Lemoine, 2000): "the FDI was considered the best option to reach three goals: increase share in international trade; get access of international capital and technology; introduce modern administrative techniques in Chinese companies".

The Foreign Direct Investment played an important role to change the production structure in China. In 1980, China had a share of 0,11% in FDI's flows, while in 2012, China's share was 9,1%. During the 1980's the major part of the FDI was related to labor intensive production, like apparel and textiles (UNCTAD, 2014). On the other hand, in the 1990's, China has led the investments towards more sophisticated products, intensive in technology. (Acioly, 2005) shows the evolution in the type of FDI:

"During the inicial period of the reform (1979-1986), investiments were concentrated in geological prospection, in labor intensive sectors, such as textiles and apparel and services sectors (real state activities). Since 1986, changed tha FDI policy in order to improve the share in transformation sectors, export led and high technology sectors." (ACIOLY, 2005, P. 25).

This change was made with technology transfer through joint ventures between chinese and international companies; the gradual openness of the Chinese economy to the global market enabling and supporting exports and local production; strong government investments in infrastructure stimulating local economy; and finally, the large government purchases with its State Owned Enterprises (SOE) to guarantee effective-demand.

Besides that, macroeconomics policies have supported this industrial transformation. Development banks have accomplished a solid credit policy (CINTRA, 2009) and an aggressive monetary policy that kept China's exchange rate depreciated in order to support local production and stimulate exports (CUNHA et al, 2007).

The unique combination of both, micro and macroeconomic policies with gradual openness to the global market can be considered as the key to this transformation. The macroeconomic policies guaranteed competitiveness for Chinese products in the international market. The depreciated exchange rate enables the country to attend global market with better prices for their products – which is very important for an industry under structural transformation. In addition to that, the easy credit system supported by development banks allows entrepreneurs to invest, expand and modernize their business, enabling the industrial structure to experience an accelerated transformation towards a more modern structure. Finally, the use of the SOEs to purchase the production stimulates the local market and completes the strategy.

All the macroeconomic stimulus to production linked to the microeconomic policies have permitted the Chinese industry to become, in less than thirty years, one of the most dynamic and modern industrial structures in the world. But, how can we measure this transformation and how modern this industry really is?

Many studies tried to understand and quantify industrial structural changes according to (Pavitt, 1984) and (OECD, 1987). Pavitt proposed a taxonomy to describe and explain sectorial patterns of technical change. After Pavitt's work, researchers have incorporated to that methodology the trade segments available at (UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics, 2010) in order to also estimate how advanced a country's industry is based on the international trade. This methodology is very usefull to compare countries, since the data follows a standardize methodology. So, to evaluate the actual structural transformation of chinese industry we compiled the Value Added (VA) available at the China's Statistical Yearbook (form 1998 to 2007) [6] to the categories proposed by other researchers who changed Pavitt's and OECD's seminal work.

For "Type of Technology" (as Table 1 shows) we adapted (Nassif, 2006) and (Lall, 2000) proposals dividing the sectors into Based on science, on Natural Resource, on Labor intensive, on Scale Intensive and Differentiated); for "Technological Intensity" we took into account (OECD, 2005) allocating the sectors into (High, Medium-High, Medium-Low and Low Technology); and for "Type of product" (SECEX/MDIC – BRASIL,2011) was used dividing the sectors into Primary, Semi-Manufactured and Manufactured. All data was deflated using the inflation rates for each sector also available at China Statistical Yearbook [7].

Table 1. China's industrial indicators – 1998 to 2007.

Years |

Industry's contribution to GDP Growth |

Technological intensity |

Type of technology |

||||||

High |

Medium |

Low |

Science Based |

Differentiated |

Natural Resources Based |

Labor Intensive |

Scale Intensive |

||

1998 |

|

10% |

55% |

35% |

4% |

19% |

35% |

15% |

28% |

1999 |

|

11% |

55% |

33% |

4% |

19% |

33% |

15% |

28% |

2000 |

|

13% |

54% |

31% |

4% |

21% |

31% |

14% |

28% |

2001 |

47 |

13% |

54% |

32% |

4% |

22% |

30% |

12% |

28% |

2002 |

50 |

13% |

59% |

25% |

4% |

20% |

34% |

7% |

33% |

2003 |

59 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2004 |

52 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2005 |

51 |

17% |

54% |

31% |

4% |

29% |

26% |

15% |

29% |

2006 |

50 |

18% |

55% |

31% |

4% |

29% |

25% |

15% |

28% |

2007 |

51 |

17% |

57% |

31% |

4% |

29% |

25% |

15% |

31% |

Source: Calculated from China Statistical Yearbooks (1998 to 2007).

It is important to mention that the Chinese industry was responsible for a large part of the country's GDP growth in the period – over 47%, consequently, the Chinese industrial catching-up process is an important part of the development strategy, since industrial gross output is a significant part of Chinese economy.

Besides that, it's possible to verify that China´s industry has raised its share in high technological sectors. The changes in the vaue added to each sector represents a structural transformation. In less than ten years, China has increased industrial share in 7 pp in sectors with more sophisticated production. This shows how China changed the scope of its production.

Moreover, the analysis of type of technology also suggest great changes in China's production. "Differentiated" sectors have increased its share in 10 pp, while "Natural Resources Based" has lost share in 10 pp in only six years. This represents the effort of policy makers to consolidate China's industry in more dynamics sectors, which are characterized by electronics components and machinery. (Nonnenberg and Mesentier, 2012, p. 311) have stressed that: "China is transforming its role in the manufacturing process of this industry. Since the beginning of the last decade, China has been able to climb the technological ladder."

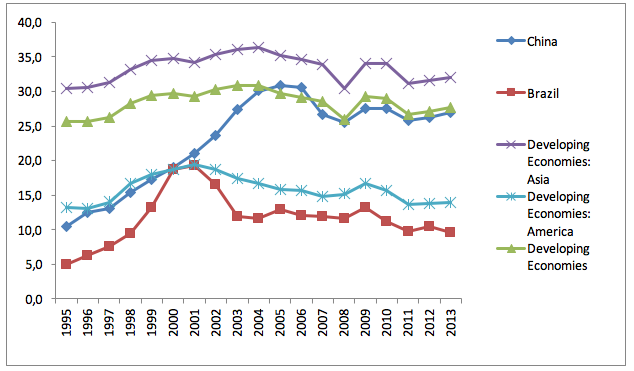

The increase in production of sophisticated products has shown results in share of exports. As shown by (Pinto, 2011, p.45): "The improvement in technological content of exports was a consequence of chinese government policy, which articulates market mechanisms with government planning mechanisms". In graphic 1, there is a comparison between Brazil and China, concerning their high technologies' exports trajectories. China and Asia have improved its exports in high technologies products, as a result of policies combination to improve production in those sectors. Meanwhile, Brazil and Latin America reduced its participation in the same period.

Graphic 1. Percentage of high technology exports, by country, 1995-2013

Data: World Bank (2014) and UNCTAD (2014).

(Rodrik, 2007, p. 7) suggests that "The hallmark of development is structural change – the process of pulling resources from traditional low-productive activities to modern high productivity activities. This is far from an automatic process, and requires more than well-functioning markets. It is the responsibility of industrial policy to stimulate investments and entrepreneurship in new activities (…)". It is known that a structural change usually takes decades to happen but what we are seeing in China is a strong transformation in a very short time. This structural change is important to promote modernization to the Chinese industry. It is also specially for China's development in a greater sense.Therefore, if we agree with Rodrik's statement we could sustain that China is on the right track to enter in the hall of developed nations.

The industrial expansion was the main driver of the income growth during the long development cycle that Brazil experienced between the 1950s and 1970s. In those years the GDP had the remarkable average annual growth of 7.4%, driven by the average 8.3% annual expansion of for industrial production (LESSA, 1983).

At the same time that the described expansion was taking place in China, the Brazilian economy was facing not just a quick quantitative growth of national income, but was also significantly successful in its effort on emulating the industrial structure of advanced economies. At the end of this cycle the Brazilian productive structure reached a high degree of diversification and sophistication, making Brazil the most successful case of industrialization in Latin America.

This long development path was suddenly interrupted in the early 1980s, when the debt crisis happened due to a combination of high oil prices associated to the U.S. interest rates shock. The adverse macroeconomic framework, with chronic high inflation, constraints in the balance of payments, high unemployment and stagnation is summarized in the idea that the 1980s is alson known as the "lost decade."

In response to this crisis the Brazilian economy, as well as other developing countries, experienced in the 1990s a series of reforms inspired by the Washington Consensus (AKYÜZ, 2005). These reforms rested on the idea that trade liberalization, privatization combined with the increase in foreign investment would lead to the Brazilian productive structure to a more efficient allocation of resources and, consequently, to a more competitive insertion in the global economy. These market-oriented reforms happened at the same time the attempt to stabilize high inflation using exchange rates anchor policies.

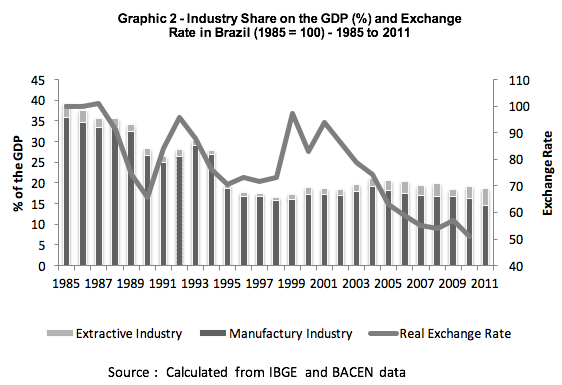

Although Brazil still has the third largest industrial GDP among developing countries - after China and South Korea (SARTI & HIRATUKA, 2011) - the downward trend in the share of the industrial sector in the GDP, is a trend contrary to the trend observed in other countries. Graphic 2 helps to identify three major events of structural change: first the neoliberal reforms of the 1990s when the industry goes from 32% to 25% of GDP, then the implementation of the Real Plan (industry share goes from 25% to 19% of GDP) and finally the 2000s with the increase in the share of the mining industry in the national income.

Despite the neoliberal belief that these reforms would lead to greater economic dynamism, there was no reversal in the context of stagnation. During the period of 1980-2003, the average annual GDP growth declined to 2% with an even lower performance of the industrial production, which grew by only 0.9% per year, on average.

In fact, the attraction of FDI had limited positive effects on economic development and the balance of payments. The majority of these investments were oriented to the domestic market (mostly non-tradable activities) and established in Brazil by purchasing early existing production structures. Moreover, subsidiaries of multinationals established by these investments are integrated in global production networks, actually increasing the import of parts and components, and other raw material.

In general, Brazilian companies have responded to this new economic environment with a defensive restructuring, promoting rationalization and expansion of imported content in their production processes. The few Brazilian companies that have ventured to internationalize through FDI are focused on traditional economic sectors, especially in services (construction and mining), reducing dynamic effects on the whole economy.

The ascent of President Lula in 2003 ended the period of economic policies guided by the Washington Consensus. However, the commitment to preserve macroeconomic stability and the inflation targeting regime was still kept. In this environment, despite the return of industrial policy initiatives in the Government agenda, the results were still weak. As (Cano & Da Silva, 2010) state,

"Due to restrictions related to macroeconomic policy, PITCE (Brazilian Industrial Policy published in the first term of President Lula) not produced the results that could, when one analyse the industry's performance as a whole and its contribution to the growth and strengthening of the Brazilian economy insertion in the international economic order, despite the good performance of some companies and sectors individually". CANO & DA SILVA (2010, p.10)

This government promoted gradual changes in the Brazilian economic policy towards the strengthening of internal market through policies for poverty reduction, recovery of employment and purchasing power of wages. These changes in the domestic market were followed by incentives that improved the international terms of trade related to growth in other developing economies, notably China. The expansion of demand in these countries for agricultural commodities and minerals boosted their prices in the international market and helped to recover the Brazilian economy.

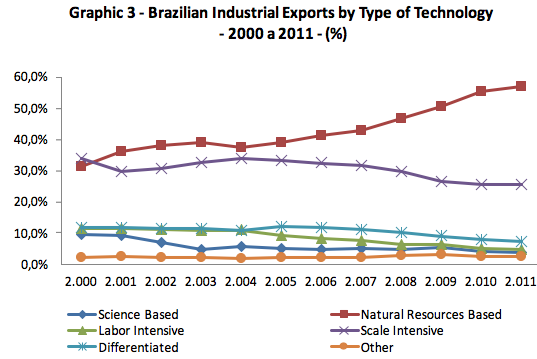

The expansion of commodity exports was important to restore, in recent years, the historical balance of payments constraints faced by Brazil. If, on the one hand, these exports were decisive to accumulate foreign exchange reserves, on other hand, they increased the specialization of exports in products intensive in natural resources. This regressive specialization on exports can be

verified on Graphic 3.

With persistently high trade surpluses as a result of the improvement of the terms of trade and the prospects for Brazil to become a major player in the world oil market, with the exploration of large reserves discovered in recent years, many economists have worried about the possibility of Dutch Disease in Brazil (BRESSER-PEREIRA, 2011).

Consequently, the Brazilian industry has displayed a quite disturbing behavior with regard to the lost of key links on some productive chains, what results in a widespread phenomenon of disintegration of historical production chains. This phenomenon is directly related to the technological intensity of sectors, with the largest decrease of productive density in science-based and scale intensive industries. Even in sectors that historically have had a fairly dense industrial structure, largely based on industrial policies, such as those related to the metal-mechanical, chemical, machinery and equipment, there was a persistent process of reducing the complexity of local supply chains.

According to (Bresser-Pereira, 2011), in order to neutralize the effects of Dutch disease in Brazil, and also in other developing economies,

"the basic policy is to impose a tax or a retention on exports of the good (or goods) that originate it; such tax will shift upwards the supply curve of theses goods; if the tax is sufficient, exports of that good that were viable at the current equilibrium exchange rate now will be only viable at the industrial equilibrium – the exchange rate level that makes viable all other tradable industries utilizing technology in the state of the art. Tariff protection does this job only partially, limited to the import side. To include the export side and make industries utilizing modern technology able to export it is required a tax on exports of the goods" (BRESSER-PEREIRA, 2011 p. 12).

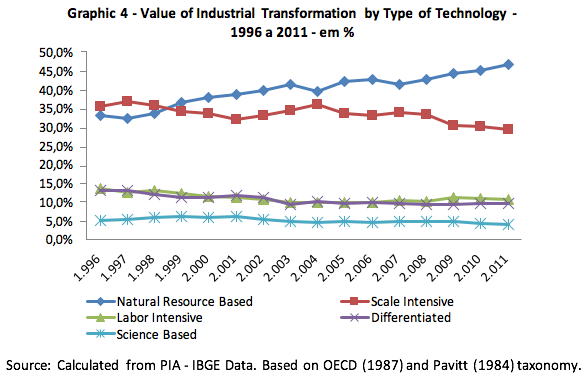

In this sense, graphic 4 shows that the Brazilian industry has focused on natural resource-intensive activities. This path has been set since the beginning of the century and has intensified by the end of the 2000s. More sophisticated segments (high added value and high transverse impacts) reduced their combined share from 53.4% to 44.3%. This is the opposite of what occurs with the Chinese industry. Analysing the disaggregated data, it is clear that the reduction is more intense the in electronics, means of production (machinery and equipment and chemical industry), pharmaceutical and intensive labor industries. Those are some of the areas in which the Chinese industry has substantially increased its global market share. Areas also affected directly or indirectly by the growth in Chinese demand as oil sector (which doubled its share in 15 years) and the extraction of minerals (333% increase) are the sectors that have increased their share in the Brazilian industry.

As a result of this process, one notes that the efforts of Brazilian policy makers to foster industrial and technological development were not enough to recovery the trajectory of economic growth based in a virtuous structural change in the terms proposed by (Rodrik, 2007). Instead, Brazilian industrial performance since 80s is related to a progressive specialization in low tech and natural resources intensive sectors, which narrows the possibilities of economic development if , as (Rodrik, 2007), we define it as the process of pulling resources from traditional low-productive activities to modern high productivity activities.

China and Brazil can be considered important examples of industrialization in developing economies. In more recent years, these economies have followed different paths of economics growth. The difference is due, in large part, to different strategies of industrial and macroeconomic policies, especially regarding to the management of exchange rate.

The Chinese development was quite successful in advancing its industrial structure towards sectors with high technological intensity, while the Brazilian economy has shown, in recent years, a regressive specialization focused on more traditional sectors.

In Brazil, the virtuous trajectory of combined economic growth with industrial diversification was stopped in the 80s and deepened as a result of liberal reforms in the 90s.

As a result of this process, we see a local movement of defensive downsizing in the most dynamic and technologically advanced sectors, and then a sharp and sustained upward trend in the concentration of industrial added value in less productive and less technology intensive sectors, based on natural resources and with a lower range of linkages (when compared to major sectors of the techno-economic paradigm of electronics).

It is also observed that, at least in part, the recent structural changes in the Brazilian economy is conditioned on the emergence of China as a major producer and exporter of high added value products.

ACIOLY, L. China Uma inserção diferenciada. Economia política internacional: uma análise estratégica [on line]out-dez, 2005, 7.[Acessed on set 2014]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/j3zMdr.

AKYÜZ, Y (2005); Trade, Growth and Industrialization: Issues, Experiences and Policy Challenges. TWN - Third World Network, Trade & Development Series, 8.

BRASIL. Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Exterior. Departamento de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento do Comércio Exterior –DEPLA. Classificação por fator agregado. [Accessed on: 16 nov. 2011]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/IVEIpX

BRESSER-PEREIRA, L. C (2011); From old to new developmentalism. In: Oxford Handbook of Latin American Economics; J. A. Ocampo and J. Ros (Eds). Oxford University Press. London, 108-129p.

CANO, W; DA SILVA, A. L. G (2010). Política industrial do governo Lula. Texto para Discussão (181); Campinas, Instituto de Economia/UNICAMP.

CHINA STATISTICAL YEARBOOK. National Bureau of Statistics. [Acessed on: 19 may 2011]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/7KlQmU.

CINTRA, M. A. M (2009); As instituições financeiras de fomento e o desenvolvimento econômico: as experiências dos EUA e da China. In: Ensaios sobre economia financeira; Ferreira, F. R. M.; Meirelles, B. B; BNDES, cap. 3, 111-149p.

CUNHA, A. M.; BIANCARELI, A. M.; PRATES, D. M. A diplomacia do Yuan Fraco. Revista de Economia Contemporânea[on line]sep/dez, 2011, vol.11. n3[Accessed on: 21 sep. 2011]. P. 525-562. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/NaLpLX

LALL, S. Technological change and industrialization in the Asian newly industrializing economies: achievements and challenges (2000); In: Technology, learning and innovation: experiences of newly industrializing economies; Kim, L. ;Nelson, R.; Cambrigde, Cambridge University Press, 260-308 p.

LESSA, C. (1983). "Quinze anos de política econômica". Ed. Brasiliense. 1- 173p.

MILARE, L. F. L (2012); O processo de industrialização chinesa: uma visão sistêmica; Sorocaba, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 1-177 p.

NASSIF, A; Há evidências de desindustrialização no Brasil?. Revista de Economia Política [on line] jan/mar, 2008, vol.28.n.1. [Accessed on: 10 nov.2011]. p. 72-96 Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/VWkWPE.

NONNENBERG, M.J.B; MESENTIER, A; Is China only assembling parts and components? The recent spurt in high tech industry. Revista de Economia Contemporânea [on line] may/aug, 2012, vol.16.n2 [Acessed on 12 sep 2014]. p. 287-315. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/4wyJZB

OECD (1987); Structural adjustment and economic performance. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.p. 371

______. OECD science, technology and industry scoreboard (2005); Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. [Accessed on: 10 nov. 2011]. p 210. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/jWR6FP .

PAVITT, K; Sectoral patterns of technical change: towards a taxonomy and a theory. Research Policy [on line] jan, 1984, 13 [Accessed on: 12 feb 2015] p. 343-373. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/Mjv3HJ

PINTO, E.C (2011); O eixo sino-americano e as transformações do sistema mundial: tensões e complementaridades comerciais, produtivas e financeiras; In: China na nova configuração global: impactos políticos e econômicos [on line] Leão, R.P.F; Pinto, E.C.; Acioly, L. A; [Acessed on: 10 out 2014]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/YSKwxS.

SARTI, F.; HIRATUKA, C (2011). Desenvolvimento Industrial no Brasil: oportunidades e desafios futuros. Texto para discussão (187), Campinas, Instituto de Economia/Unicamp, 1-33 p.

UNCTAD (2010); Handbook of statistics . [Acessed on: 15 feb. 2011]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/9JtqPf

WORLD BANK (2014); [Acessed on: 20 apr 2014]. Available at World Wide Web: http://goo.gl/VFkcXm.

1. Coordinator of GPETeD, Research Group in Economics, Technology and Development, Department of Economics, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil, Email: acdieguesgues@ufscar.br

2. Department of Economics, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil, Email: cesarcruz@ufscar.br

3. Member of GPETeD, Research Group in Economics, Technology and Development, Department of Geography, Humanities and Tourism, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil, Email: jeroselino@gmail.com

4. Tax auditor at Regional tax Office (DRTC-III), São Paulo State Finance Secretary, Brazil, Email: luismilare@gmail.com

5. Member of GPETeD, Research Group in Economics, Technology and Development, Master Candidate in Economics at Department of Economics, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil, Email: carolembm@gmail.com

6. Data concerning value added was available for years: 1998,1999,2000,2001,2002,2005,2006 and 2007.

7. For the complete methodology see MILARE (2012).